In this post:

- Marduk Chiasm and Genesis 1:26-28

- The Tell-Fekherye Inscription (9th c. BC)

- Does God Look Like Man?

- What is Man to Do?

In the previous part of this series, I noted that the creation of man in Genesis 1 has significant parallels to Enuma Elish that need their own post to do them justice. We will explore those parallels and their meaning here.

Marduk Chiasm and Genesis 1:26-28

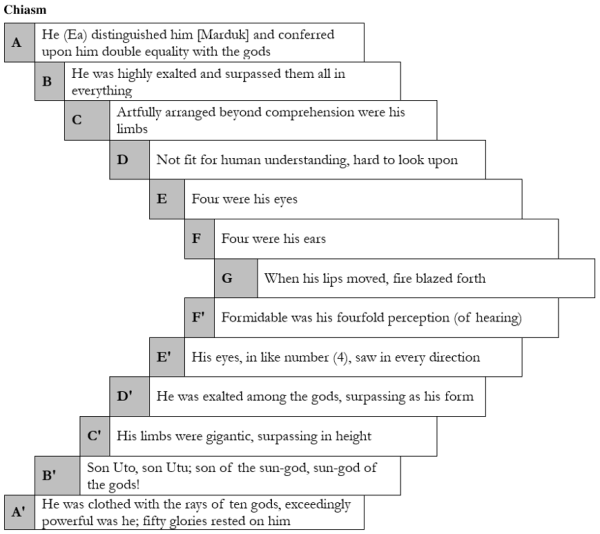

In the story Enuma Elish, the hero of the story who defeats the dragon and recreates the universe according to his desire is Marduk. Without question, he is the main focus of the entire story. Part of what signifies his importance early on in the story is the amount of space and literary detail that is put into the story of his creation. Below, you will see that an introductory section that describes Marduk’s birth and his attributes is followed by a chiasm that details his attributes.

Introduction

In the temple of destinies, the abode of designs, the most capable, the sage of the gods, the lord was begotten, In the midst of Apsu Marduk was formed, In the midst of sanctuary Apsu was Marduk formed! Ea his father begot him, Damkina his mother was confined with him. He suckled at the breasts of goddesses, The attendant who raised him endowed him well with glories. His body was splendid, fiery his glance, He was a hero at birth, he was a mighty one from the beginning! When Anu his grandfather saw him, He was happy, he beamed, his heart was filled with joy.

In each corresponding section, the author returns to the same topic. So, since section E talks about his four eyes, section E’ talks about his four eyes again. When we turn to Genesis, we see that a similar but shorter structure is found describing the creation of man:

Introduction and Summary

Then God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness so that they will have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.” So God created man in his own image:

We can see that both Genesis and Enuma Elish introduce the creation of the most significant figure in their stories with an introductory section that is followed by a chiasm that goes over the attributes of the created individual again but in greater detail. We should understand Moses as indicating that the most important creation in the Genesis narrative is mankind. In Enuma Elish, Marduk was the most important creation in the universe and humanity was made to be a pathetic slave that did the work that the gods did not want to do. Moses’ use of the same literary structure reverses the roles; humanity is the highlight of creation, while the heavenly beings (what we call angels) are not significant enough to get more than a passing mention (discussed in the next post).

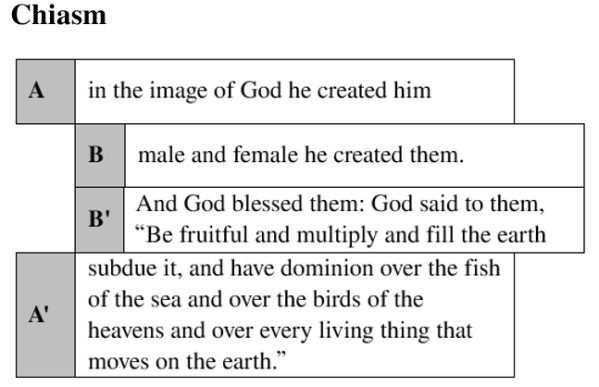

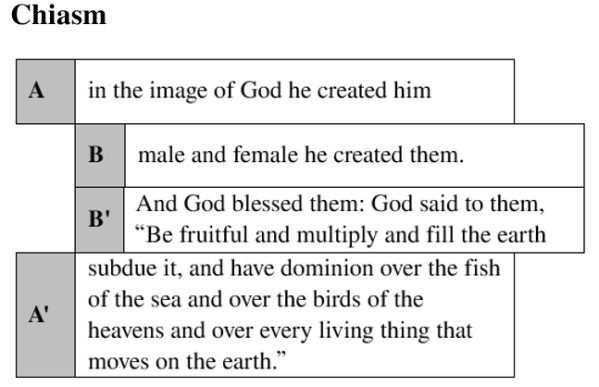

If you carefully consider the structure of the Genesis chiasm, you will notice that while the word likeness is found in the introduction, it is not found in the chiasm. We can either understand this as indicating that the B and B’ parts of the chiasm relate to image in a way that was so obvious to the original audience that the author felt it was unnecessary to be overt about the matter, or we can understand likeness as no longer being part of the conversation. Evidence from the Tell-Fekheriye Inscription clarifies this matter for us.

The Tell-Fekheriye Inscription (9th c. BC)

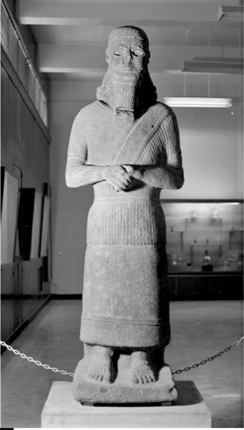

The Tell-Fekheriye inscription, which is written on the skirt of the statue in the above picture, reveals that the words image and likeness had unique nuances in the ancient world. The text of this inscription is found below for the reader’s consideration.

To Adad:

The likeness of Hadad-yis’i which he has set up before Hadad of Sikan, regulator of the waters of heaven and earth, who rains down abundance, who gives pasture and watering places to the people of all cities (to all lands), who gives portions and offerings (rest and vessels of food) to (all) the gods, his brothers, regulator of (all) rivers, who enriches the regions (all lands), the merciful god to whom it is good to pray, who dwells in Guzan (Sikan),

to the great lord, his lord, Adad-ifi (Hadad-yis’ï), governor (king) of Guzan, son of Shamash-nun (Sas-nun), also governor (king) of Guzan, for the life of his soul, (and) for the length of his days, (and) for increasing his years, (and) for the prosperity of his house, (and for the prosperity) of his descendants, (and for the prosperity) of his people, (and) to remove illness from his body (from him), for hearing my prayer (and for making his prayer heard), (and) for accepting my (his) words,

he devoted and gave (he set up and gave to him). (And) whoever afterwards shall repair its ruined state (shall raise it to erect it anew), may he put my name (on it). (And) whoever erases my name (from it) and puts his name, may Adad (Hadad), the hero, be his adversary

The image of Adad-ifι (Hadad-yiskï) governor (king) of Guzan, (and of) Sikan, (and of) Azran, for perpetuating (exalting and continuing) his throne, (and) for the length of his rule, (and) so that his word might be pleasing to gods and to people, this image he made better than before.

Before Adad (Hadad – storm god) who dwells in Sikan, lord of the Khabur, he has set up his image. Whoever removes my name from the furnishings of the house of Adad (Hadad), my lord, my lord Adad (Hadad) shall not accept his food and water from him (from his hand), my lady Shala (Sawl) ditto (shall not accept his food and water from his hand); (and) may he sow, but not harvest; (and) may he sow a thousand measures (of barley), (and) may he take a se’ah (a fraction from it);

(and) may one hundred ewes suckle a lamb, but it not be satisfied; (and) may one hundred cows not satisfy a calf (suckle a calf, but it not be satisfied); (and) may one hundred women bakers not fill an oven (one hundred women bake bread in an oven, but not fill it); may the gleaner glean in a refuse pit (and, may his men glean barley from a refuse pit, and eat), may disease, plague, the staff of Nergal, not be cut off from his land.

The careful reader will notice that the image is set up with the hope that the deity will bless the king with an exalted and extensive reign that involves people and gods being pleased by the king’s commands (meaning, the people follow his orders and the gods do not oppose his decrees). By contrast, the likeness is set up with the hope that the deity will bless the king with a long life, a healthy body, a large family, a large nation, and prayers that are favorably received by the divine. In short, image relates more to the idea of royal rule over the world, while likeness has more to do with personal attributes and progeny.

Let’s return to the Genesis text again:

We saw the word image in the Tell Fekheriye inscription had to do with royal rule, and we see that the blessing/obligation to subdue the world and take dominion is aligned with image. We also saw that likeness has to do with personal attributes and progeny, and in Genesis we see that being made male and female aligns with the blessing/obligation to multiply and fill the earth. So, the B and B’ sections of the chiasm do expand upon what likeness means in the introduction.

If we look back to the Marduk Chiasm, we see that the beginning and end of the chiasm (steps A-D and D’-A’) focus more upon how Marduk relates to the others (he ten times better than them in every way and beyond human comprehension) while the middle of the chiasm (steps E, F, G, F’, and E’) relates more to his personal attributes (fully perceptive and attentive, with words of power). This is seen in the Genesis structure as well, with image indicating how man relates to others in the world and likeness having more to do with personal attributes.

Does God Look Like Man?

Although we have focused on the distinct nuances of image and likeness, it is important for us not to miss the fact that both terms have to do with an object that represents the divine. We should not, however, conclude that this text indicates that man’s body looks like God’s body. In a study of royal statues, Irene Winter concluded that statues were not meant to accurately portray what a king looked like. Instead, they were meant to symbolically portray abstract attributes like wisdom, power, dignity, etc. So, our bodies are made to symbolically portray abstract attributes.

What is Man to Do?

It was commonly understood that a being made in the image of a god comes with the obligation to accurately represent that deity both in his public rule of that God’s domain and in his personal activities. In the text below, we see that the king shouldn’t want to be outside during the night since he is the image of the sun god.

LAS 143 o. 14–r. 6 (K 583; from the time of Esarhaddon, 681–668 BC)

Why, today already for the second day, is the table not brought to the king, my lord? Who (now) stays in the dark much longer than the Sun, the king of the gods, stays in the dark a whole day and night, (and) again two days? The king, the lord of the world, is the very image of the Sun god. He (should) keep in the dark for only half a day!

The king, being the image of the sun deity, ought to be spend more time outside during the day. The personal attributes of the king should correspond to the personal attributes of the deity. This relationship is often referred to as the king being the son of the god whose image he shares, or even being called by the name of that God. Through a covenantal relationship, the king is granted and obligated to be like the god whose image he possesses.

In the text below, we see that the king executes his royal rule based on how Marduk behaves.

SAA 8:333 (82-5-22,63; from the period 697–665 BC)

The wisest, merciful Bel, the warrior Marduk, became angry at night, but relented in the morning. You, O king of the world, are an image of Marduk; when you were angry with your servants, we suffered the anger of the king our lord; and we saw the reconciliation of the king

Just as Marduk was angry for a night but became calm in the morning, so the king appropriately imaged him by being angry for a short time but then ceased to be angry afterward. These texts might give the impression that image has to do with personal attributes. However, it is common for terms to develop generic use alongside specific use. Consider how the word “cow” is used to refer to both female cows and male cows, although it technically refers to female cows. So, “image” on its own refers to both image and likeness, but when both words are used together, there is a distinct meaning to each, as we saw on the Tell Fekheriye inscription.

Conclusion

Moses carefully crafted the creation story of Genesis 1 to indicate that mankind was the highlight of creation and simultaneously backgrounded the heavenly host, an action that corrected the erroneous teaching in Enuma Elish that the heavenly host is of primary importance while man is just a pathetic slave. Moses also communicated man’s rule in the world through the commonly understood ideas of image and likeness: mankind is to represent God’s character and ethics as they rule over God’s domain (the world).

Leave a comment